Risk, Mitigation, and Contingency

Source: Unsplash

Understanding risks is an important part of production, and it’s often overlooked. You might not think about the factors that will negatively impact your development plan until something goes wrong: you have a conflict in your version control that takes time to resolve, your game engine updates and introduces some confusing bugs you need to fix, or a key team member is suddenly unavailable. By the time these problems appear, it’s often too late to respond without delays, stress, or cutting scope.

Proper risk planning turns surprises into manageable challenges. When you know what could go wrong, how likely it is, and how severe its impact will be, you can plan ahead. This reduces the impact that risks will have or, in some cases, makes it less likely they will occur at all.

Risks vs Known Constraints

Risks are uncertain events that might happen and that would have a negative impact on your ability to complete your project. There are many different types of risk, including:

Technical risks (e.g. tools producing inconsistent results, tech debt or legacy code causing unexpected issues, engine updates introducing bugs or breaking functionality, experimental tech being unpredictable etc.)

Production risks (e.g. external approvals taking longer than planned, assets arriving late or needing rework, pipeline changes disrupting workflow etc.)

Team risks (e.g. key staff being unavailable due to leave, illness, or competing priorities, miscommunication between departments leading to rework, new team members requiring onboarding or extra iteration time, etc.)

External risks (e.g. power outages, internet down time, hardware failures, sudden budget or funding changes, etc.)

Every project has risks, so your risk register should never say “our project has no risks”.

But remember, events that are guaranteed to occur—such as platform certification processes, public holidays, or exam periods—are not risks, because they are certain. These known constraints should be included in production schedules and roadmaps directly, rather than in your risk register.

Similarly, dependencies are not risks in themselves, as they are expected. However, they can create risk if they are not properly tracked and managed.

Risk Matrix

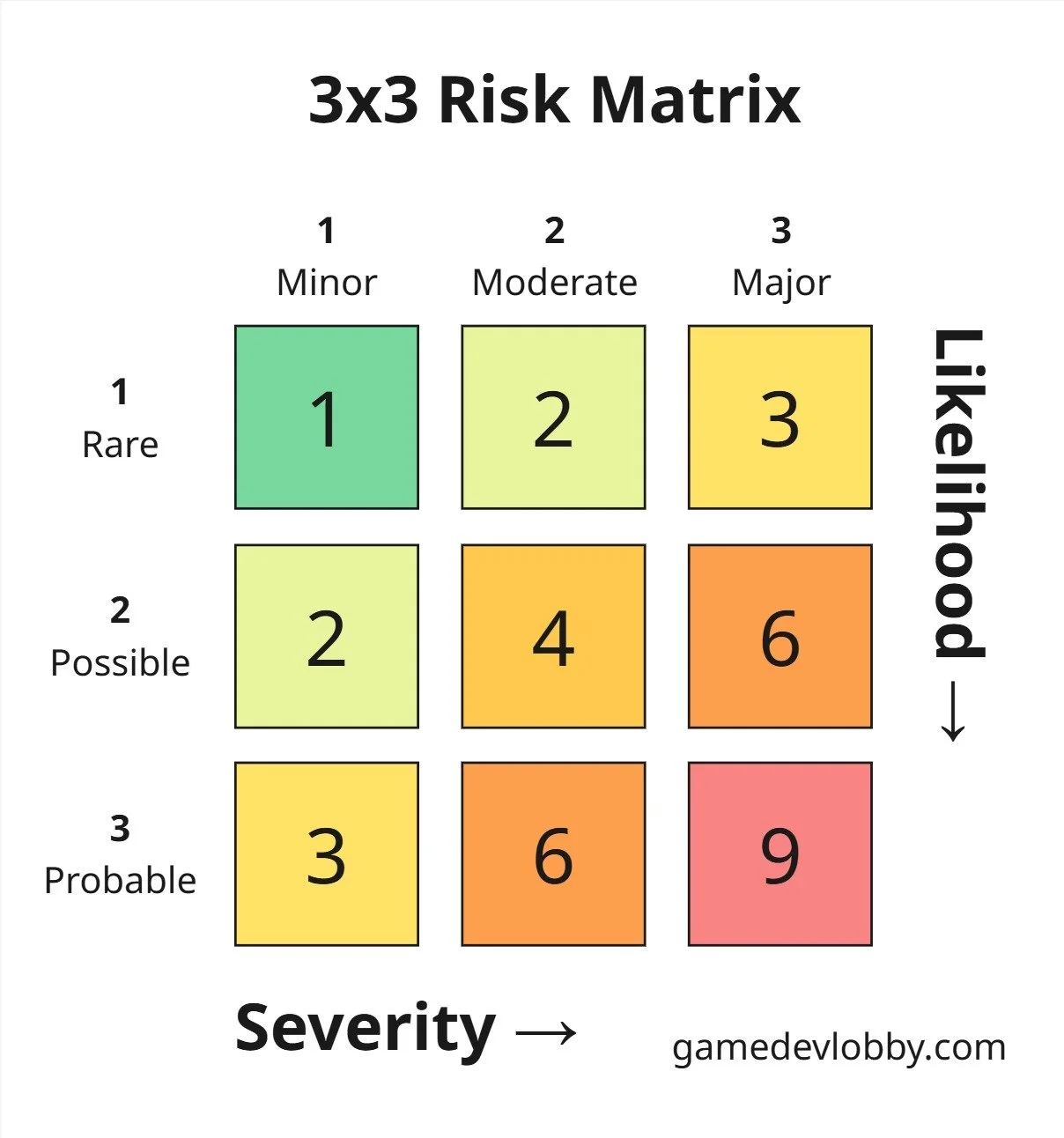

One of the simplest and most effective ways to track risks is with a risk matrix. This matrix helps you visually identify which risks matter most in terms of their likelihood and severity.

Likelihood describes the probability of a risk occurring, while severity describes how bad the impact will be if it does occur. Risks that have both high likelihood + high severity get the highest score and are considered critical risks that require immediate action.

The goal is to reduce the score of all risks as much as possible by reducing the chance of them occurring and planning responses that will minimise their impact. Risks with a lower score on the risk matrix can be logged and monitored, but don’t require the same urgent attention.

Tracking Risks

Risks are not static: they change over time as a project evolves through the stages of production.

Risk registers are documents used to track active risks, their current score, the intended response to them, contingency plans, and relevant notes. On larger teams, they might also be a place to track risk owners, as well as the teams, disciplines, or projects that the risk impacts.

When estimating new features or introducing new technology, make sure relevant risks are added to the risk register. Review the document regularly, such as during sprint planning or milestone reviews. The goal should be to reduce the score of risks over time—using strategies to reduce their likelihood and severity—or to be able to remove risks from the register entirely.

Responding to Risk

There are six key ways producers and developers can respond to risk:

Escalation: The risk is escalated to somebody with more authority to advise on next steps (a studio head, manager, creative director, etc).

Transference: The risk is transferred to another team or department who is better suited to deal with its mitigation and consequences.

Avoidance: Action is taken to fully avoid the risk. For example, if a plugin is causing an issue in a build, the plugin is removed entirely and a different tool is used. Note that this may remove one risk, but may simultaneously introduce new challenges.

Mitigation: Action is taken to partially avoid the risk, downgrading its score by reducing its severity or likelihood. For example, prototyping early to test experimental technology, breaking large tasks into smaller deliverables to catch problems sooner, or building redundancy by training more than one team member who can handle a critical task.

Active acceptance: No action is taken to avoid the risk; however, proactive steps are taken to deal with the potential repercussions of that risk occuring. For example, pre-emptively planning how to communicate to stakeholders that a milestone will need to be delayed, in case a team member becomes unexpectedly unavailable. Instead of planning to avoid or reduce the delay, active acceptance focuses on what to do if the delay occurs.

Passive acceptance: No action is taken to avoid the risk. The risk continues to be observed and monitored, but no plans are made to act in response to the risk at all.

Contingency

Even when we use techniques to reduce the likelihood or severity of a risk, some risks will still occur. Contingency planning involves proactively figuring out the ‘next steps’ rather than needing to respond to a crisis reactively.

For example:

If a critical dependency is blocked, your contingency plan may be to switch focus to other work that can progress in parallel.

If a deliverable is delayed, you might plan to reduce scope or substitute temporary placeholders so progress can continue.

If team capacity suddenly decreases, you might have a process for reprioritising tasks or deferring non-critical features.

Contingency plans work best when you attach buffers to your schedule. Reserving additional time for responding to problems without derailing the whole project will also reduce the severity of risks.

Learn more about Estimates for Emerging Devs →

Conclusion

Maintaining an up-to-date risk register helps ensure you are prepared for interruptions and issues. By identifying risks, prioritising them using a risk matrix, and proactively planning your response and contingencies, you protect your project from stressful surprises.

For students and emerging developers, building an early habit of identifying and interrogating risks will set you apart. It shows that you think ahead, communicate clearly, and respect both your team and your stakeholders. Remember that successful teams aren’t the ones that manage to avoid problems; rather, they see problems coming and have a plan before they arrive.